Supply, Demand and Marketplaces

In every business, there’s only a handful of activities that deliver the bulk of the value to the organisation, Pareto’s 80/20 principle.

If you’re running a marketplace, one such activity is managing supply and demand. Too much supply leaves you with unproductive, potentially costly assets; demand significantly outstripping supply leaves you with unhappy customers going elsewhere.

Managing supply and demand is partly tactical, day-to-day ops stuff, but there’s also a substantial strategic component. The “design decisions” a company makes cascade out into every part of the business, these kinds of decisions are a force multiplier that can work for you, or against you.

Background:

Technology is deflationary by nature; advances in technology consistently translate into reduced search and transaction costs for the economy.

A great example of this phenomenon has been the digitisation of marketplaces. Some of the most valuable companies of the last 15 years are service marketplaces like Airbnb and Uber.

The original digital marketplace model was far more transactional, acting purely as an intermediary, facilitating the connection of two parties and nothing more. Over time advances in technology allowed for a new model to emerge that expanded to cover a greater proportion of the transaction.

Rather than simply introducing two parties and cutting ties, some marketplaces began to facilitate the entire transaction end-to-end, taking payment, and dealing with cancellations, refunds and complaints.

As far as the customer is concerned, they’re dealing with a single company. This allows a business to build a brand that can engender loyalty without having to employ lots of people (the gig economy) or own any assets (the sharing economy).

The success of Uber inspired an entire generation of entrepreneurs to create marketplaces for everything from property and loans, to hairdressers and therapists.

To succeed, marketplace businesses must manage supply and demand effectively: volume, quality, fit and margin.

One simple solution is to rely on fully flexible supply the way Uber does. This way, the business only incurs a marginal cost for every transaction facilitated and the cost of building the supply base will be an order of magnitude lower than having to actually own the supply.

For a business like Uber, this makes complete sense, however, as we’ll see here, it’s a model born out of necessity not desire.

To understand the dynamics of a marketplace there are a few important concepts to understand.

The Transaction Profile:

Each individual transaction in a marketplace can be broken down into a few core concepts, each of which has implications for how supply and demand are best managed.

- Lead Time: The period of time between an individual making a request to the marketplace and the point they’d ideally like the transaction to take place.

- Transaction Window: The period of time that an individual is willing to accept either side of their ideal transaction time.

- Degree of Heterogeneity: What makes for an acceptable match between supply and demand. The more heterogeneous the market the more difficult it will be to find a good enough match.

The Demand Profile:

While the transaction profile represents a single transaction, the demand profile represents the aggregate of all the transactions.

At the aggregate level, there are three important aspects to consider when deciding how best to manage supply and demand:

- Variability: Is demand consistent over time or does it fluctuate? How high are the peaks in demand?

- Predictability: How predictable is demand? If demand is going to vary, can you at least predict that ahead of time?

- Fixed Cost Base: How much investment is required to establish the supply base? Very high fixed costs are obviously undesirable, particularly for an early-stage company.

To make things a little less abstract, let’s consider these concepts for Uber vs Task Rabbit, the service marketplace for on demand helpers (e.g. DIY):

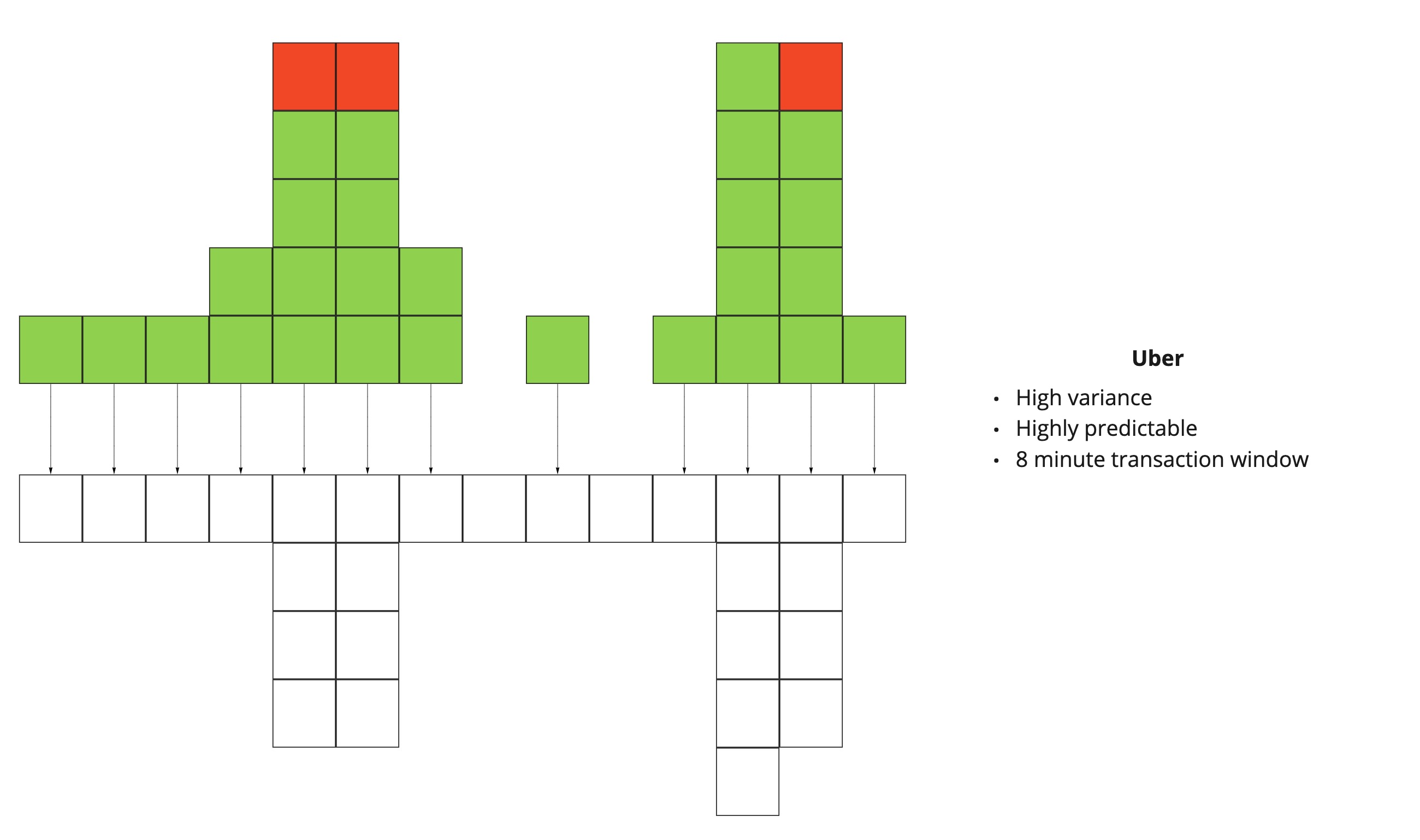

Uber:

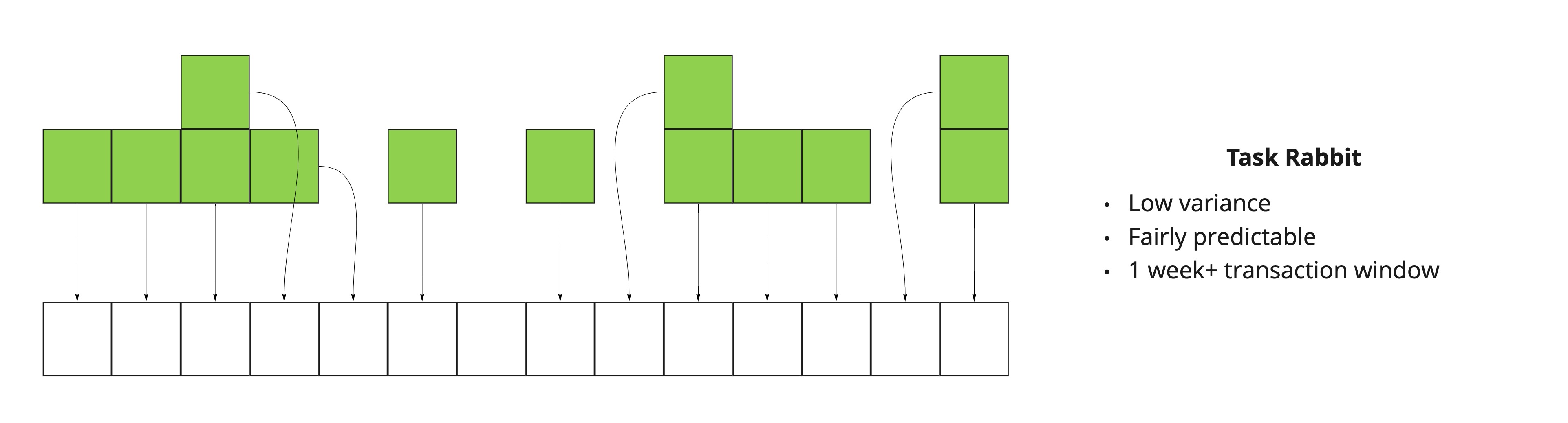

Task Rabbit:

Taken together we can start to see why a fully flexible model makes sense for Uber. The super-tight transaction window (~8 minutes) means they can’t distribute the demand over a flatter supply curve - supply ends up being tightly coupled to demand. This coupled with the highly variable nature of demand (huge surges on weekend evenings) makes it impossible to justify a move to a less dynamic supply network.

At this point, you might be wondering what’s wrong with fully-variable supply?

Multi-Homing:

Coined by Hamilton Helmer, this describes the scenario where your customers can frictionlessly participate in multiple networks simultaneously. When your supply multi-homes, it has a series of negative impacts on your ability to manage supply and demand effectively:

- Your supply is now shared between multiple pools of demand that you have no visibility of and as a result, you no longer have an accurate understanding of your own supply.

- In scenarios where market participants form an ongoing relationship, you would ideally control the flow of demand to a supplier in order to prevent over-demand. Efforts to do so are futile when another network can simply use up that supply.

- Similarly, with exclusive supply, you can schedule transactions efficiently to minimise waste but when supply is shared the chances of unwanted gaps appearing in a schedule are both out of your control and more likely to occur.

- So far we’ve only discussed the incidental effects that result from shared supply. You also have to consider that a competitor could, in theory, preemptively buy up supply as a competitive strategy strangling your own supply. Similar dynamics existed between Uber vs Lyft in the early days and the bigger competitor will always have the upper hand.

- Finally, if your suppliers create a differentiated experience, then they are a valuable resource. Multi-homing allows your competitors to reap the same benefits. Sharing supply means you are diluting your ability to use that as the basis for any kind of competitive advantage.

Unit Economics:

The more demand you guarantee for a supplier the lower per-unit cost (to a certain point) they are willing to transact for. It’s the simple concept of a bulk discount. This is one of the benefits of a (semi) fixed supply base. Conversely moving towards a fully flexible supply base will cause your unit economics to degrade as the suppliers essentially remove the bulk discount, leaving you with the choice, do you accept thinner margins or raise prices?

There is also a second-order effect. If you guarantee no work for a supplier, your LTV from any single supplier becomes less certain (and likely decreases). This combined with degraded unit economics makes it riskier to invest in your supply, effectively encouraging you to have a much more transactional, lighter-touch relationship with your suppliers. How can you offer supplier training or mentoring, or stomach a high supplier acquisition cost if you struggle to know if you can get a return on that investment?

Wrap Up

Managing supply and demand boils down to trying to get the supply and demand curves to match as closely as possible in a cost-effective manner.

This is much easier to do when demand is both predictable and stable as opposed to tightly coupled and highly variable.

Understanding the dynamics of both your supply and demand and what levers you have available to impact these (e.g. business model, demand allocation, marketing, demand segmentation and supply elasticity) is super important for any marketplace.

Making the wrong choice is likely to compress your margins, create operational inefficiencies and expose you to unnecessary competitive pressure. It’s an important design decision and one that many companies seem to overlook.

It’s not that the Uber model is never the answer, but most companies operate in markets vastly different from the on-demand, capital intensive and geographically bounded taxi space, yet they blindly copy Uber’s model…